In Scala you can write pure functional code, similar to Haskell or other pure functional languages, but you’re not obligated to. Wikipedia categories Scala as an impure Functional language.

FP purists view this as a weakness of Scala, but others view the option of “cheating” pureness as an acceptable choice sometimes. Even if you can do everything purely, it’s sometimes a lot easier to think about the problem in a different paradigm.

Pure FP is great for writing correct functions you can easily reason about in isolation and compose well with other pure functions. We can easily unit test them since pure functions only depend on their input arguments and always produce the same output for the same arguments – they are referentially transparent.

This allows the programmer and the compiler to reason about program behavior as a rewrite system. This can help in proving correctness, simplifying an algorithm, help change code without breaking it, or optimizing code through memoization, common sub-expression elimination, lazy evaluation, or parallelization.

There are, however, other approaches to thinking about compossibility of programs.

One such approach is to think of software components as black boxes running a process.

They have a variable number of input and output ports which have Types associated to them.

Messages pass asynchronously from component to component after linking their corresponding ports together (if the types match).

We specify the connections outside the components themselves.

This is the thinking behind flow based programming.

(This is also how microservices work at a larger scale)

My view is that these two ways of thinking about composable programs are not mutually exclusive and they can work together in synergy. I will try to make this case by the end of this post.

Pure Functional Programming in Scala

Using Cats, you can use Type Classes: Functor, Applicative, Monad etc… to model your programs based on these highly general computational abstractions.

There are other ecosystems for pure FP in Scala. I chose Cats because I’m most familiar with it.

Adding Cats-effect, you can also model IO in a pure functional way. The idea is to write the entire program, including all the effects like: calling external services, writing to file, pushing messages to queues, as a single composed expression that returns an IO data structure representing the action of running all these effects, without actually running them. You only execute them at the “end of the world” in the “main” method.

This is a simple example of a pure functional program using cats-effect.

import cats.effect.{ IO, Sync }

import cats.implicits._

import scala.io.StdIn

object App {

def getUserName[F[_]: Sync]: F[String] =

for {

_ <- Sync[F].delay(println("What's your name?"))

name <- Sync[F].delay(StdIn.readLine())

} yield name

def greatUser[F[_]: Sync](name: String): F[Unit] =

Sync[F].delay(println(s"Hello $name!"))

def program[F[_]: Sync]: F[String] = for {

name <- getUserName

_ <- greatUser(name)

} yield s"Greeted $name"

def main(args: Array[String]): Unit = {

program[IO].unsafeRunSync()

}

}Real programs will, of course, be much more complex, but it all boils down to a single IO value that combines all the effects of running the program which we execute in the “main” method.

Runar has a great talk where he compares using pure FP and IO as working with unexploded TNT. That is much easier to work with as opposed to working with exploded TNT (by actually executing effects in each function).

Stream processing in Scala

Akka Streams implements the Reactive Streams protocol that’s now standardised in the JVM ecosystem.

Streams have added benefits over simple functions by implementing flow control mechanisms which include back-pressure.

You can think of streams as managed functions, similar to how the Operating System manages threads.

A stream component can decide when to ask for more input messages to pass to its processing function, how many parallel calls to the function to allow, and whether to slow down processing because there is no demand from downstream functions.

Akka is using the abstractions of Source, Flow, Sink for modeling streams.

A Source is a Component that has one output port and generates elements of some type.

A Sink is a Component that has a single input port that consumes elements of some type.

A Flow is a combination of a Sink and a Source having a single input and single output port. We can think of a Flow as a processor transforming a message into another.

A big difference from normal functions is that the number of input messages does not have to match the number of output messages…

For instance, a Flow can consume 1 input messages but produce 2 output messages (or none). In that sense, Flows differs greatly from functions – which will always produce an object of its return type given input arguments (assuming it throws no exceptions. For pure functions this should hold).

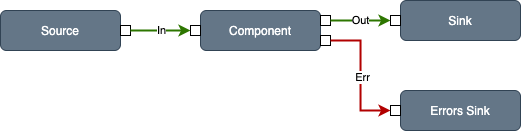

Those are the simplest components, but we can write more complex ones. For instance – components having a single input port but two output ports.

I like to model failure in components like this: I use the first output port as the normal (success) output, and the second one as the error output. For a single input, only one of the output ports yield a message.

What I like about Akka Streams is the ability to compose components using the Graph DSL. The way you write code can be very intuitive, as it’s almost a one-to-one match with drawing boxes and links between them. Architects and devs are quite familiar with this way of thinking, so it seems very natural.

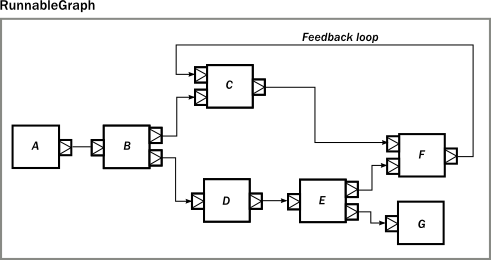

Here’s an example of using Graph DSL to write a complex stream.

(The code and graph image representation are from the Akka Streams documentation)

import GraphDSL.Implicits._

RunnableGraph.fromGraph(GraphDSL.create() { implicit builder =>

val A: Outlet[Int] = builder.add(Source.single(0)).out

val B: UniformFanOutShape[Int, Int] = builder.add(Broadcast[Int](2))

val C: UniformFanInShape[Int, Int] = builder.add(Merge[Int](2))

val D: FlowShape[Int, Int] = builder.add(Flow[Int].map(_ + 1))

val E: UniformFanOutShape[Int, Int] = builder.add(Balance[Int](2))

val F: UniformFanInShape[Int, Int] = builder.add(Merge[Int](2))

val G: Inlet[Any] = builder.add(Sink.foreach(println)).in

C <~ F

A ~> B ~> C ~> F

B ~> D ~> E ~> F

E ~> G

ClosedShape

})

Other stream processing frameworks in Scala like fs2 don’t have such DSL’s, and it may be difficult to write certain kinds of flows.

For instance, if you have a loop from a downstream component to an upstream one, we can easily model this with Akka Graph DSL but not as easily with fs2.

Combining Cats and Akka

The Idea is simple: use pure functions to write all the business code and effects (like external system calls, db calls etc…) in IO using Cats and Cats Effect.

I’ll add some Case Classes and mocked functions so we have something to work with in the examples below:

def parseMessage[F[_]: Sync](msg: String): F[Message] =

Sync[F]

.delay(msg.split('|'))

.map(split => Message(id = split(0), userId = split(1)))

def getUser[F[_]: Sync](userId: String): F[User] =

if (userId == "123")

Sync[F].pure(User(userId, "Mihai", "me@mihaisafta.com"))

else

Sync[F].pure(User(userId, "John", "John@example.com"))

def checkPermission[F[_]: Sync](user: User): F[Boolean] = user.name match {

case "Mihai" => Sync[F].pure(true)

case _ => Sync[F].pure(false)

}

def sendNewsletter[F[_]: Sync](user: User): F[Unit] = for {

nl <- Sync[F].pure(NewsLetter(user.name, "Hello, this is the newsletter"))

_ <- Sync[F].delay(println(s"Sent newsletter: $nl to user $user"))

} yield ()

def sendNewsletterIfAllowed[F[_]: Sync](user: User, userPermission: Boolean): F[Unit] =

if (userPermission)

sendNewsletter(user)

else

Sync[F].delay(println(s"Not sending newsletter to $user"))We could write a pure FP program to run these steps sequentially

def program[F[_]: Sync](msg: String): F[Unit] = for {

message <- parseMessage(msg)

user <- getUser(message.userId)

allowsEmails <- checkPermission(user)

_ <- sendNewsletterIfAllowed(user, allowsEmails)

} yield ()But now let’s see how we could wrap each step using Akka Streams.

Since Akka Streams can’t work in a purely functional style, we have to execute the effects of the operation in each part of the flow… we can’t remain in the pure functional programing style of constructing a single IO and running it only once. We are moving from the pure FP world into the Flow Based Programming World.

Source(List("1|123", "2|123", "3|789"))

.mapAsync(parallelism = 8)(m => parseMessage[IO](m).unsafeToFuture())

.mapAsync(parallelism = 8)(m => getUser[IO](m.userId).unsafeToFuture())

.mapAsync(parallelism = 8)(u => checkPermission[IO](u).map(p => (u, p)).unsafeToFuture())

.mapAsync(parallelism = 8) { case (u, p) => sendNewsletterIfAllowed[IO](u, p) }

.runWith(Sink.seq)Notice that we have to call the “.unsafeToFuture()” method in each “.mapAsyncUnordered” step.

I think of it like each step in the stream is a “main” program itself.

Just like how the OS manages your processes and threads, here the stream manages your pure functions. We only use the stream for wrapping functions, sending messages through the sequence of wrapped functions and applying flow control.

Not for domain logic, which we write only in pure functions.

Using parallelism set to 8 means that each step can process 8 messages in parallel without blocking the upstream steps.

If the “sendNewsletter” call is slow, it will create back-pressure up the chain until it reaches the Source which will stop sending more messages until there is demand again.

Back-pressure is a key benefit of streaming.

It guarantees that fast producers don’t overwhelm slow consumers, which could lead to issues from degraded performance to crashes caused by out of memory exceptions.

Without streaming technology, you need to implement back-pressure yourself to get the same guarantees… Pure FP or even Actor based systems don’t have that built in.

Conclusion

This is the first part in a series of post where I explore how to connect pure functional programming using Cats and Streaming with Akka Streams.

So far we’ve seen that you can write pure functions and embed them in Akka streams using “.mapAsync”. You also have to run the effects inside each step using “.unsafeToFuture”

In the next parts we’ll see how to simplify the interaction between pure functions and Akka stream – by abstracting the need to call “.unsafeToFuture” every time.

Also, we’ll construct more complex component and use the Akka GraphDSL to combine them in interesting ways.

Hope this helps 😀

Please leave comments or suggestions on this Reddit thread, and get in touch with me on Twitter.