In the last post, we saw how to combine pure functions running in IO and Akka streams using .mapAsync and .unsafeToFuture

val source: Source[String, NotUsed] = ???

val sink: Sink[Int, NotUsed] = ???

def pureFunction[F[_]](s: String): F[Int] = ???

source

.mapAsync(parallelism = 8)(m => pureFunction[IO](m).unsafeToFuture())

.runWith(sink)In order to make it easier to work with IO in Akka Streams, we can write some helpers to add a method on Streams that automatically run the IO inside the flow. This will simplify the interaction between pure code and stream code.

Readability will improve, but before we get there, it’s very important to recognise that we should view these 2 ways of writing code[1]Pure code and Streams code as having orthogonal purposes.

Streams as plumbing

The philosophy is identical to how Unix pipes work.

You write small pieces of code using simple programs like: ps, grep, find, sed, awk, xargs, kill etc… and join those smaller programs into a bigger one by piping data between them. The output of one program goes into the input of the next.

There is a clear separation of duties between programs that do something[2]Programs that do some work and have side effects and pipes that just pass data along between programs.

Here’s an example of a pipeline that finds all java processed and stops them:

ps aux | grep java | grep -v grep | awk '{ print $2 }' | xargs kill -9The similarity between this and Akka flows is almost one to one[3]The difference is that Unix pipes have 2 output streams: STDOUT and STDERR. In Akka flows, you only have one output as a stream – which is for successful processing. It throws errors out of … Continue reading.

One issue in Scala is that we write both the program and the pipeline / stream in the same language, which can blurry the separation of concerns…

For this reason, some people don’t see why we should separate these two ways of writing the full program.

My view is that we should try to separate them logically to get to the simple way of composing programs like using Unix Pipelines.

My suggestion here is to have separate modules for the domain, and Classes with pure functions working on the domain that run certain actions.

After constructing those Classes (which can be individually unit-tested), write a Class taking the other domain and functionality Classes as constructor arguments.

This Class should just combine all the individual pure functions by wrapping them in Akka flows, but nothing more. No extra business logic other than the order of operations…

Simplify Cats and Akka interaction

Assuming we understand the separation of concerns between pure functions and streams, we still want to make their combination easy. Maybe as easy as the Unix pipe.

The first step is to simplify using .mapAsync and IO.

What we need is another method on Akka streams that automatically runs the IO[4]We can be more generic by using the Effect type constraint instead of IO directly inside the Flow by transforming it into a Future.

We can enable this generically by wrapping a source or flow in extension classes with the extra method: .unsafeMapAsync

implicit class SourceExtensions[A, Mat](val source: Source[A, Mat]) extends AnyVal {

def unsafeMapAsync[F[_]: Effect, B](parallelism: Int)(f: A => F[B]): source.Repr[B] =

source.mapAsync(parallelism)(b => Effect[F].toIO(f(b)).unsafeToFuture())

}

implicit class FlowExtensions[A, B, Mat](val flow: Flow[A, B, Mat]) extends AnyVal {

def unsafeMapAsync[F[_]: Effect, C](parallelism: Int)(f: B => F[C]): flow.Repr[C] =

flow.mapAsync(parallelism)(b => Effect[F].toIO(f(b)).unsafeToFuture())

}The method name shows we are running the effect which is unsafe[5]Because it executes side effects – similar to the method name .unsafeToFuture

This is the split between pure FP and Akka streams. We are now in streaming territory where we run the effects in each flow step.

Now we can rewrite the code from the previous post.

Source(List("1|123", "2|123", "3|789"))

.unsafeMapAsync(parallelism = 8)(m => parseMessage[IO](m))

.unsafeMapAsync(parallelism = 8)(m => getUser[IO](m.userId))

.unsafeMapAsync(parallelism = 8)(u => checkPermission[IO](u).map(p => (u, p)))

.unsafeMapAsync(parallelism = 8) { case (u, p) => sendNewsletterIfAllowed[IO](u, p) }

.runWith(Sink.seq)Notice the lack of calls to .unsafeToFuture()

Much cleaner.

Another refactor we can do is to extract individual flows in values – same as we could do with functions, but in this case they are Flow types.

val parseFlow = Flow[String].unsafeMapAsync(8)(parseMessage[IO])

val getUserFlow = Flow[Message].unsafeMapAsync(8)(m => getUser[IO](m.userId))

val checkPermissionFlow = Flow[User].unsafeMapAsync(8)(u => checkPermission[IO](u).map( (u, _) ))

val sendNewsletterFlow = Flow[(User, Boolean)].unsafeMapAsync(8) {

case (u, p) => sendNewsletterIfAllowed[IO](u, p)

}And then use the .via method to combine them in a bigger flow

val flow = parseFlow

.via(getUserFlow)

.via(checkPermissionFlow)

.via(sendNewsletterFlow)Looks much closer to the unix pipeline example, so I’m happy 😃.

We construct the full stream using .via to connect the Source and Sink as well

Source(List("1|123", "2|123", "3|789"))

.via(flow)

.runWith(Sink.seq)We can go a step further and use the GraphDSL

val flow = Flow.fromGraph(GraphDSL.create() { implicit builder =>

import GraphDSL.Implicits._

val Parse = builder.add(parseFlow)

val GetUser = builder.add(getUserFlow)

val CheckPermission = builder.add(checkPermissionFlow)

val SendNewsletter = builder.add(sendNewsletterFlow)

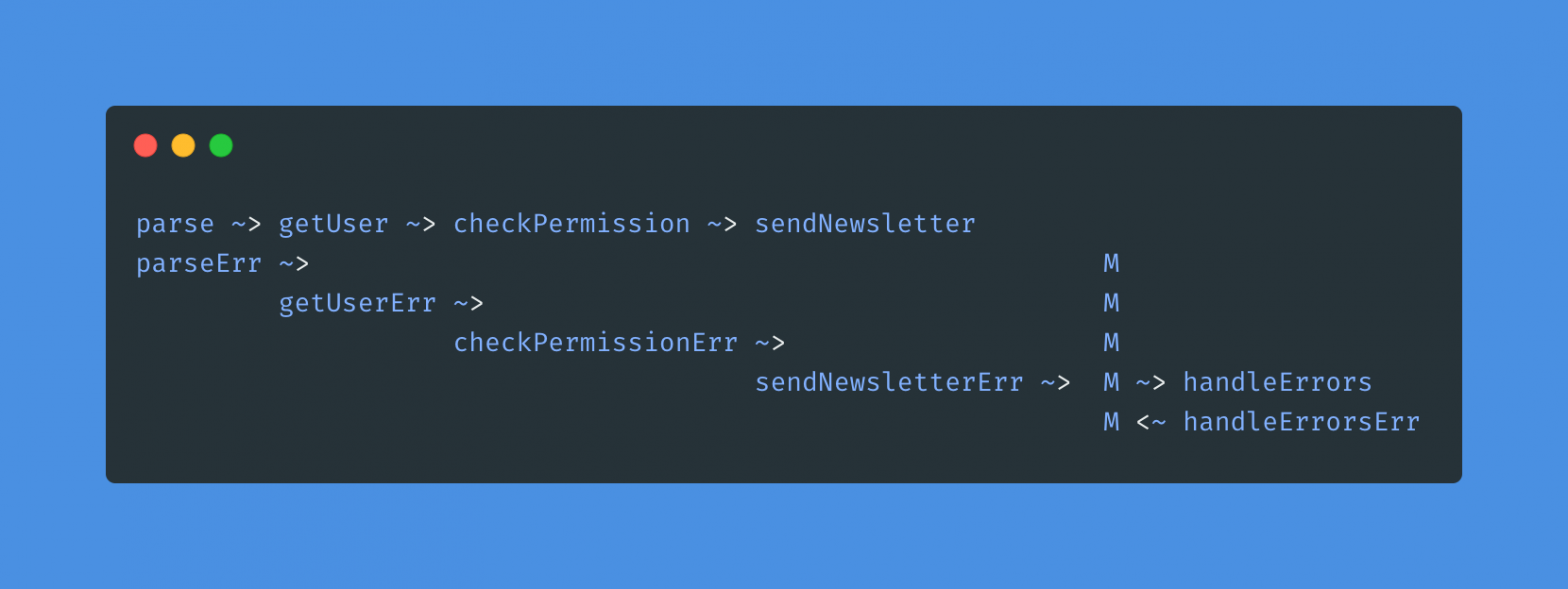

Parse ~> GetUser ~> CheckPermission ~> SendNewsletter

FlowShape(Parse.in, SendNewsletter.out)

})Here we add the flows as nodes in the Akka Graph, then join them together in a single flow using Akka’s GraphDSL and the ~> operator.

The result is a graph with the Shape of a Flow – one input, out output. We can create an actual Flow from the graph with the constructor: Flow.fromGraph

Notice how similar the expression:Parse ~> GetUser ~> CheckPermission ~> SendNewsletter

Is to a unix pipeline. Just replace ~> with | and it’s the same.

It’s also very similar to something we might draw to represent this flow.

I think this is one of the significant advantages of using Akka streams and the GraphDSL – you can look at the actual code to see the computational graph instead of looking at representations of it. It’s not drawn by someone else, which can also become outdated quickly. The code does not lie, a representation can.

The major difference between the GraphDSL and using .unsafeMapAsync directly is that we separate individual graph nodes from their connection to other nodes – similar to the idea in Flow based programming. This allows for higher flexibility.

If there are multiple implementations for a component with the same interface, we can easily just swap the component to the new one, but the graph structure remains the same.

The GraphDSL allows us to create more complex computational graphs than this simple one.

For this one, it is of course easier to use the simpler version from the first example.

Complex graphs

So far we haven’t looked at how to treat errors in the stream…

If we do nothing, for any exception thrown in the stream, Akka will simply silently ignore them… There are methods to deal with that the Akka way.

However, let’s look at what we can implement to make sure the stream never stops processing but we still handle errors. We can do that because we’re in control of the way we execute the effects in the stream.

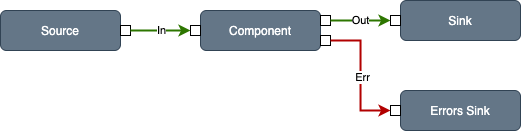

We can design a different stream component that will catch exceptions in the IO and push it on a separate error stream – similar to the STDERR of Unix.

To achieve this we can add another extension method on Flow and Source which will run the effect but return a component with a specific output for the Error, if there is any error thrown in the effect.

implicit class FlowExtensions[A, B](val flow: Flow[A, B, NotUsed]) extends AnyVal {

// ...

def safeMapAsync[F[_]: Effect, C](parallelism: Int)(

f: B => F[C]

): Graph[FanOutShape2[A, C, Throwable], NotUsed] = {

split[A, Throwable, C](

flow.mapAsync(parallelism)(b => Effect[F].toIO(f(b)).attempt.unsafeToFuture())

)

}

}We’ll call this safeMapAsync since we know w’re catching exceptions as part of the graph.

The logic behind is just calling .attempt on the IO, which will return an Either[Throwable, C] . We then split the Either into the 2 separate outputs of the new Graph.

The return type here is no longer Flow, but it’s a Graph with the shape: FanOut with 2 outputs: Graph[FanOutShape2[A, C, Throwable], NotUsed]

The input is of type A, normal output type is C and error output is Throwable.

The helper method for splitting the Either is a bit more verbose… but it’s very generic, so you only have to write it once.

def split[A, E, B](flow: Flow[A, Either[E, B], NotUsed]): Graph[FanOutShape2[A, B, E], NotUsed] =

GraphDSL

.create() { implicit builder =>

import GraphDSL.Implicits._

val F = builder.add(flow)

val B = builder.add(Broadcast[Either[E, B]](2))

val LeftBranch = builder.add(Flow[Either[E, B]].collect {

case Left(b) => b

})

val RightBranch = builder.add(Flow[Either[E, B]].collect {

case Right(c) => c

})

F ~> B ~> LeftBranch

B ~> RightBranch

new FanOutShape2(F.in, RightBranch.out, LeftBranch.out)

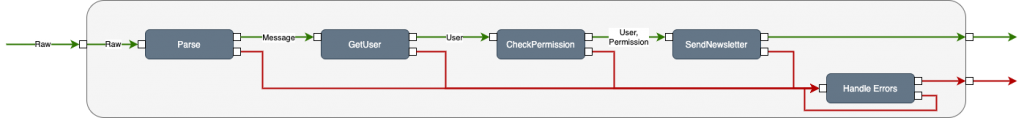

}Now we can again rewrite the original stream to capture the error outputs and merge them into a generic error handling flow.

First, we need to update the components to use .safeMapAsync

val parseComponent = Flow[String].safeMapAsync(8)(parseMessage[IO])

val getUserComponent = Flow[Message].safeMapAsync(8)(m => getUser[IO](m.userId))

val checkPermissionComponent =

Flow[User].safeMapAsync(8)(u => checkPermission[IO](u).map( (u, _) ))

val sendNewsletterComponent = Flow[(User, Boolean)].safeMapAsync(8) {

case (u, p) => sendNewsletterIfAllowed[IO](u, p)

}We then write the graph using these components

GraphDSL.create() { implicit builder =>

import GraphDSL.Implicits._

val (parse, parseErr) = toTuple(builder.add(parseComponent))

val (getUser, getUserErr) = toTuple(builder.add(getUserComponent))

val (checkPermission, checkPermissionErr) = toTuple(builder.add(checkPermissionComponent))

val (sendNewsletter, sendNewsletterErr) = toTuple(builder.add(sendNewsletterComponent))

val (handleErrors, handleErrorsErr) = toTuple(builder.add(handleErrorsComponent))

val M = builder.add(Merge[Throwable](5))

// format: off

parse ~> getUser ~> checkPermission ~> sendNewsletter

parseErr ~> M

getUserErr ~> M

checkPermissionErr ~> M

sendNewsletterErr ~> M ~> handleErrors

M <~ handleErrorsErr

// format: on

new FanOutShape2[String, Unit, Throwable](parse.in, sendNewsletter.out, handleErrors.out)

}The toTuple[6]def toTuple[I, O, E](<br> g: FanOutShape2[I, O, E]<br> ): (FlowShape[I, O], Outlet[E]) = {<br> val Err = g.out1<br> val Success = g.out0<br> … Continue reading helper just recreates a Flow for the success path and a separate Source with the errors from the FanOutShape2 graph to make it easier to connect.

If we look at this drawing of this graph and compare it with the code, we’ll see that they are quite similar

Notice that the newly constructed Graph is itself a FanOutShape2 graph. We could embed it in a higher level graph. Structural composition of graphs is easy, they compose hierarchically.

Also note that we have a loop from the error output of the error handler itself. This may come as a surprise… we could have side-effects in handling errors like sending a notification to PagerDuty or an email. These effects could fail themselves if the called service is down…

If we wrote the code in a more traditional manner, we might even miss seeing this loop[7]which could lead to unfortunate things like messages stuck in an infinite loop, hogging CPU and memory, but now that we see it explicitly, we can do something about it[8]making sure to handle errors in the loop so they don’t cycle infinitely.

In my case, the handleErrorsComponent function prints the exception, but also throttles the stream so that if there are many errors happening, the whole stream will go into back-pressure and start taking fewer input messages.

val handleErrorsComponent =

Flow[Throwable]

.throttle(1, 1.second)

.safeMapAsync(8)(t => println(t))Because the error data flow is explicit in the stream, the graph becomes more verbose than before.

I don’t see this as a problem, in fact, I see it as a plus since many issues with systems occur because of poor error management.

Having explicit error output forces you to deal with them. The graph needs to be fully connected, so the errors have to go somewhere.

Having a generic error handling flow is a good place to start, and just merge all errors in this flow. We can conceive more complex scenarios where you can handle different error types in different flows. Just connecting the error outputs to the specific error handler component can configure it.

Conclusion

In this post, we find how to create Akka flows from pure functions in a syntactically cleaner way, with the help of some extension classes over Source and Flow.

We also see how to construct more complex components and stitch them together using the GraphDSL.

In future posts, I’ll explore more patterns of constructing and combining components.

Coments thread on Reddit: https://www.reddit.com/r/scala/comments/lotklb/pure_functional_stream_processing_in_scala_cats/

References

| ↑1 | Pure code and Streams code |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Programs that do some work and have side effects |

| ↑3 | The difference is that Unix pipes have 2 output streams: STDOUT and STDERR. In Akka flows, you only have one output as a stream – which is for successful processing. It throws errors out of bound – you don’t have an error stream |

| ↑4 | We can be more generic by using the Effect type constraint instead of IO directly |

| ↑5 | Because it executes side effects |

| ↑6 | def toTuple[I, O, E](<br> g: FanOutShape2[I, O, E]<br> ): (FlowShape[I, O], Outlet[E]) = {<br> val Err = g.out1<br> val Success = g.out0<br> (FlowShape(g.in, Success), Err)<br> } |

| ↑7 | which could lead to unfortunate things like messages stuck in an infinite loop, hogging CPU and memory |

| ↑8 | making sure to handle errors in the loop so they don’t cycle infinitely |